Two Nature papers use 'novel spin-squeezing technique' for ultra-precise quantum measurements

The exotic quantum phenomenon known as "entanglement" can link atoms and other particles, allowing them to interact instantaneously regardless of distance. New research suggests that it is possible to take advantage of entanglement to create more accurate and faster quantum sensors that could support satellite navigation technologies such as GPS.

Quantum sensors rely on the effects that can occur, as the universe can become blurred even at the smallest viewpoint. These quantum effects are vulnerable to outside interference. However, quantum sensors capitalize on this vulnerability by reacting to the slightest disturbance in the environment.

Quantum sensors are increasingly reaching unprecedented levels of sensitivity and accuracy, and their potential applications include detecting magnetic fields, discovering hidden underground structures and resources, helping lunar rovers detect oxygen in moon rocks, and listening for radio waves emitted by dark matter.

Atomic clocks are the most accurate timepieces available and can also be used as quantum sensors. Similar to the principle that a grandfather clock keeps time by swinging a pendulum, atomic clocks monitor the vibrations of atoms. Optical atomic clocks use laser beams to capture and monitor atoms, and are currently accurate to 1 attosecond - one billionth of a second.

In addition to timekeeping, atomic clocks have many possible applications. For example, they are key to the precise timing signals relied upon by the Global Positioning System (GPS) and other global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) to help users pinpoint their location.

Now Ana Maria Rey, a quantum physicist at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) and one of the senior authors of the new study, explains that entanglement could theoretically help improve quantum sensors. When individual atoms are used as quantum sensors, they generate inherent noise as they move between energy states. However, when atoms are entangled, they behave in a consistent way that reduces the noise; this makes the signal from the entangled atoms clearer, which improves the actual measurements and reduces the time needed to get reliable results.

In theory, entanglement can link particles at opposite ends of the universe. In practice, it is difficult to entangle atoms that are far apart. Atoms interact more strongly with those closest to them; the farther away they are, the weaker the interaction. Scientists would like to increase the maximum entanglement distance between particles because it would also increase the total number of particles they can entangle.

In their new study, Rey and her colleagues have developed a new way to entangle atoms despite their distance from each other. Rey says, "This opens up a way to model infinite distance interactions."

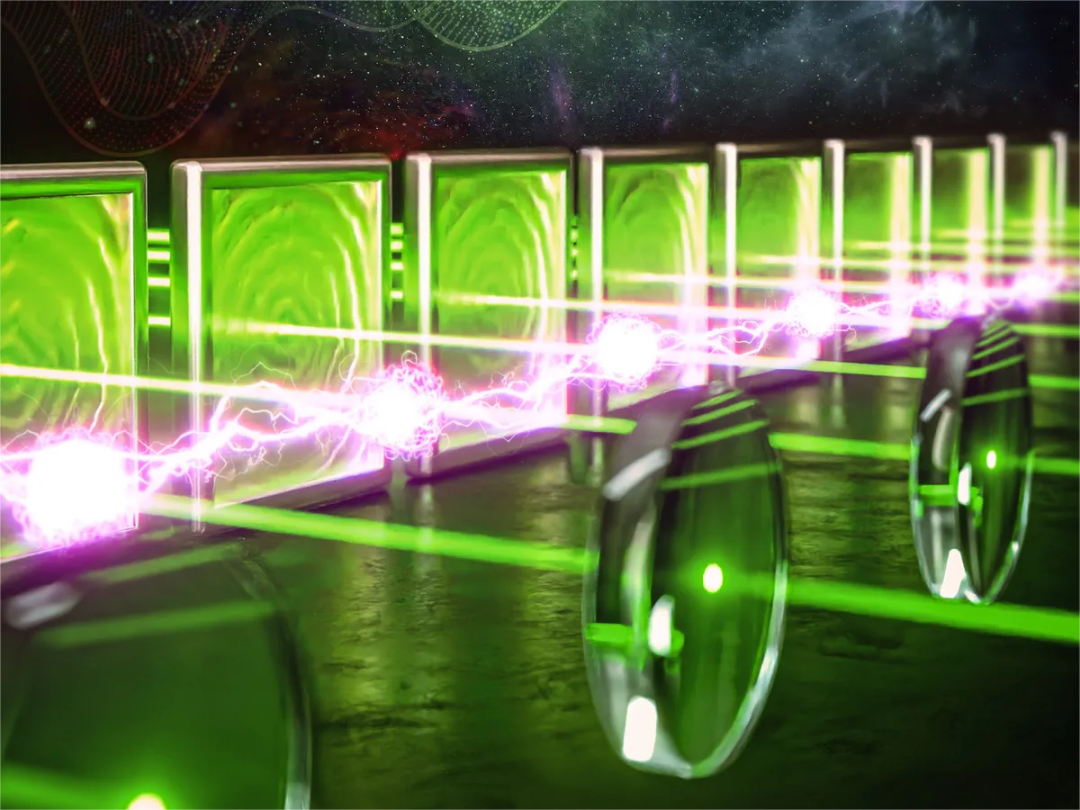

In the experiment, the scientists lined up 51 electrically trapped calcium ions, each about 5 microns apart. They used a laser to generate quasiparticle vibrations called phonons in the ions. These phonons move down atomic lines so they can share quantum information and become entangled.

One way to create entanglement is through a process known as spin squeezing. All objects that follow the rules of quantum physics can exist in multiple energy states at the same time, an effect known as superposition. Spin-squeezing reduces all these possible superposition states to a few possibilities in some ways, and expands them in others.

In a very short time, interacting ions become entangled and form a spin-squeezed state. However, over time, they transform into "cat states". These states consist of pairs of states that are diametrically opposed to each other, like the blurred states of life and death experienced by the famous thought experiment "Schrödinger's cat". According to Rey, cat states are highly entangled, making them particularly suitable for sensors.

Previous studies have designed static links between atoms, where each atom can only interact with a specific array of ions. In the new study, however, the scientists detuned the lasers to produce a magnetic field that causes the links to change over time: this means that atoms that initially can only interact with one set of atoms can eventually turn around and interact with all the other atoms in the array.

Christian Roos, another senior co-author of the study and a quantum physicist at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, said, "We showed for the first time how to generate entanglement that can scale with the number of particles."

Roos said the scientists found that their new technique could reduce noise in sensors by a little more than a factor of two using 12 ions. Rey concurs, "In the future, the plan is to trap ions in a two-dimensional arrangement rather than a linear chain, which could help trap more ions, speed up the dynamics, and produce better entanglement."

All in all, the researchers hope to apply this strategy "to state-of-the-art clocks that can trap thousands of particles in three-dimensional arrays, thus in principle making the most accurate sensors ever.

Optical atomic clocks could also benefit from spin-squeeze entanglement. In another study, a group of researchers, also based at Boulder, used lasers to hold strontium atoms in a two-dimensional plane. Finely controlled beams called optical tweezers placed the atoms into groups of 16 to 70 atoms each. Using a high-powered ultraviolet laser, the scientists excited the electrons of these atoms into Rydberg orbits away from the nucleus.

The high-energy nature of Rydberg orbitals can lead to strong interactions between atoms, such as mutual entanglement. Using spin-squeezing, scientists have created entanglement in arrays of up to 70 atoms.

Clocks using these entangled arrays showed signal-to-noise ratios that were about 1.5 times higher than those shown by unentangled clocks. Adam Kaufman, senior author of the study and a physicist at CU Boulder, said that this increase in precision can also be explained by an increase in speed: the entangled clocks took half as long as the unentangled clocks to reach a given measurement precision.

Kaufman also said that future research could explore other methods of generating entanglement besides spin-squeezing to see if they could improve measurement accuracy.

- 2023-08-04

- 2023-07-15

- 2023-07-12

- 2023-06-16

- 2023-06-12

- 2023-06-01

- 2023-05-31

- 2023-04-25

- 2023-04-18

- 2023-03-02

- 2023-02-17

- 2023-02-16

- 2023-02-15

- 2023-01-11

- 2022-11-16